I arrived alone at sunset. Campus was still except for a light breeze that carried in the humid smell of marsh. It was August 11, 1995, the day before the Class of 1999 was due to report, and I’d shown up for knob year early on the assumption that a single day—12 hours, really—wouldn’t make a difference. I was wrong.

That morning I’d boarded a flight from upstate New York carrying a lacrosse stick and a duffel bag that was ridiculously and impossibly large—a bag sized beyond any hope or sense of practicality—stuffed with everything an arriving knob was supposed to have, including two pairs of pajamas. I didn’t own pajamas—what 18-year-old does—so the two pair stuffed deep into the shadowy folds of my olive green bag had to be borrowed from my great-grandfather. Well, not exactly borrowed. My great-grandfather, Edwin Schumacher, whose own story intersects with ours just briefly and only on this particular point, had died 14 years earlier, and for some reason my mother had retained his pajamas as a keepsake. Now they’d been crammed in with everything else and then slung into the belly of an American Airlines jet bound for Charleston. The flight was scheduled to last four-and-a-half hours, with a brief layover in Charlotte. The second plane never came.

Rerouted, repurposed—recycled for all I knew—the plane simply vanished, and we were left to wonder when another might be scrambled to rescue us from North Carolina. I paced the terminal, carrying my lacrosse stick and a fresh copy of The Guidon, the pocket-sized publication that contains everything a fourth-class cadet is supposed to know. That summer I’d memorized The Guidon but failed to break in my shoes, which was not only a failure to prioritize, but Exhibit A in long list of exhibits that would have highlighted, had I been paying attention, just how little sense I had of precisely what lay ahead. A family returning from the Caribbean noticed first my lacrosse stick—they found it vaguely exotic—and then, when I stopped to talk, The Guidon. This, they knew. They were from West Ashley,* an area that in 1995—and, frankly, to a lesser extent, even now—was to me a geographical black hole; it sucked in all understanding of place and direction, and returned nothing. They asked what company I was in. This struck me as strange. I paused long enough to show just how strongly I disagreed with their syntax, then explained that as a serious college student I was unemployed and therefore not part of any company at all. We quickly sorted out that in fact I was in a company—F-Troop—which meant I’d be living in second battalion. They knew Padgett-Thomas Barracks as the big one with the clock tower that had old horse stalls buried beneath it. They talked about cadre and hell week and knobs and how cadets were known to climb the Coburg Cow. They kept bringing up Pat Conroy, which made me wonder what the guy who’d written The Prince of Tides had to do with The Citadel.

Eventually, a plane arrived and carried us to Charleston, and this family opened themselves up to me, as so many South Carolina families would over the years. They gave me a ride, they gave me hugs, they gave me their number—I lost it in those chaotic first weeks and never spoke to them again—and then they left me in the shadow of second battalion.

A day early. Academic orientation, one of 99 firsts, wasn’t scheduled to start until the morning, so nobody was expected. Why my parents stuck me on a plane for Charleston without first bothering to check the schedule is a mystery. Why I didn’t double-check myself, however, isn’t—I’m not a details guy. Even now, decades later, if forced to book my own itinerary to hell, I’d probably still arrive, totally by accident, earlier than required. The sophomore on guard, young and skinny and barbarically shaven, met me coolly—no talk of Coburg Cows or Pat Conroy or Whatever Ashley—and asked what company I was in. This time I answered correctly, and a phone call was made. Moments later, a confused F-Troop clerk wandered down. He wore a black cadre t-shirt that clung to his sloped shoulders and stared at me as if I’d just dropped from the sky. He looked at the guard—all but swallowed up under his white summer leave hat—then back to me. “Grab your bag,” was all he said.

Struggling under the enormity of my bag, I spiraled my way up two flights of stairs to what was technically the third floor but—because second battalion has that whole complicated Band thing—was actually considered the second. The clerk threw my door open and said there was a vending machine and a bathroom at the end of the hall but that I probably shouldn’t use either. I should stay in my room, he said, with the door closed and maybe even the light out. He said it wasn’t safe out there for me, which really didn’t make me feel good about being there at all, let alone early. As he turned to go, something on his clipboard caught his eye. He stopped. “Your roommate’s Corps Squad,” he said. I asked what that meant. “Means it’s gonna be a long and lonely week.”

Despite the warnings, I left my door open. It was Charleston. In August. In an old barracks without air conditioning. That room was an oven. The clerk reappeared, this time with a guitar slung over his shoulder. He stood there, a lone minstrel in PT shorts, softly plucking at the strings. I waited but he didn’t say anything. Just stared at me. It was excruciating. And unending. He never blinked, never spoke, never moved anything but his fingers. Finally, I stood and moved slowly across the room to shut the door.

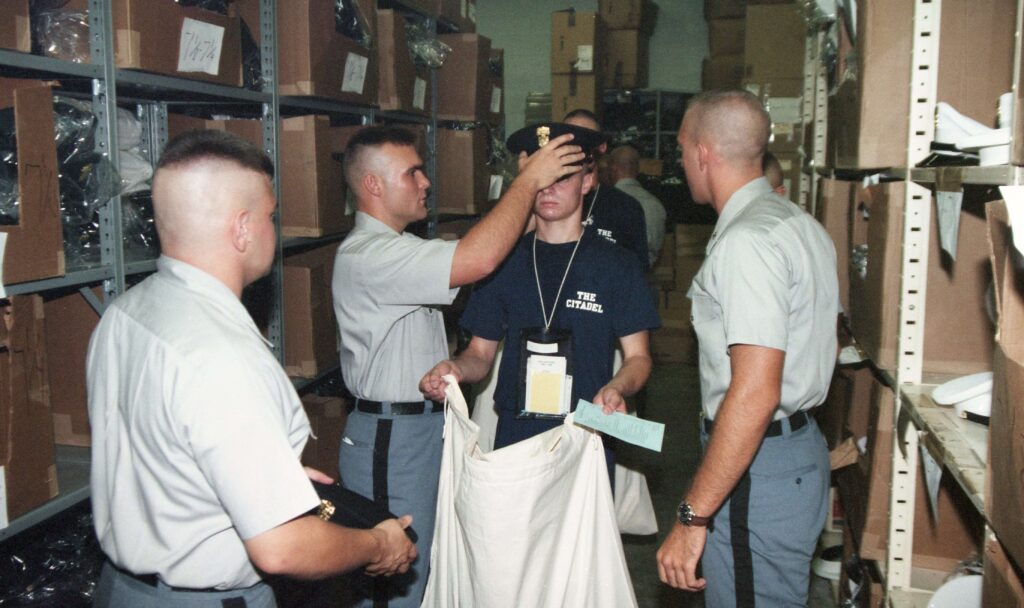

You know what happened from there. The sun rose and the rest of 1999 reported. We spent two days in academic orientation—a bewildering weekend that seemed to serve little purpose other than to drive up the cadre’s desire to tear flesh from our bones. Which they did the following Monday. We learned to brace, we learned to march, we ran laps around campus. A dozen times a week we passed the water tower where someone had painted “Conroy Sucks,” and all I could think was, Man, these guys really hate The Prince of Tides.

Eventually, we were recognized, became sophomores, then juniors and after that we got our rings. We graduated and walked off into a sunset that promised military glory or civilian careers, where we’d become husbands and maybe fathers who looked back—fondly, for the most part—on our time at school and the memories we shared.

At least, that was the plan.

Among the things I didn’t know back in the summer of 1995 was that another incoming knob was about to make a much more momentous arrival than I had. Shannon Faulkner, who’d recently won her two-and-a-half-year legal battle with the school, became the first female cadet to matriculate. She checked herself into the infirmary on the first day of cadre and by week’s end she was gone. The entire Corps was called to McAlister Field House where a member of the administration leaned into the microphone and bellowed, “Gentlemen of the Corps of Cadets… Let me repeat that. Gentlemen of the Corps of Cadets.” Out came the Save the Males bumper stickers and the t-shirts. We were congratulated and toasted and could go nowhere without someone—more often than not a middle-aged woman—leaning in close to whisper that she was glad Faulkner had quit.

Whatever lessons we took from all this unraveled a year later when an even bigger scandal occurred. Suddenly we were antiquated, we were animals—we were the problem. MTV did live feeds from the parade deck. Cadets downtown had drinks thrown in their faces. We were called again to McAlister, not for a congratulatory pep rally—forget what was said last year—but to be scolded. Experts arrived to lecture us on hazing, sensitivity and sexual harassment. Officials from an all-female university were brought in to explain diversity, and one of our classmates stood up and asked, in a surprisingly even tone, “What gives you the right?” Few words could’ve summed up our frustration so sweetly.

But it was in our junior year that all the issues buried back in ’95 finally came to the surface. By then the Class of 1998 had become seniors, and they quickly and loudly planted their flag as the last class. Specifically, the last all-male class. They boasted of being the last to matriculate without women and, with the announcement that Nancy Mace would walk the stage a year early with us, the last to graduate without them as well. They even tried (briefly and unsuccessfully) to be the last class with Summerall Guards.

Theirs was a very specific reaction to the tremendous changes taking place, and it seemed—to many of us in ’99—not only futile, but self-defeating. We had failed to learn from our mistakes in 1995 and couldn’t afford to do it again. We would not spend our senior year grasping at the past when instead we should be looking to the future.

That future was certainly all around us on ring night, where one of the speakers was Brig. Gen. Emory Mace—not only commandant, but Nancy’s father. Gripping the podium, voice breaking, he told us exactly what that ring meant to him and what he’d done to keep it. I’ll let the details of that speech remain in memory, but the essence of what he said was that the principles behind the ring mean something only if the people wearing it carry them forward. In other words, you don’t get to choose your challenges, but you sure as hell get to choose how you deal with them.

I could think of no more apt summation to the unique journey of the Class of 1999.

The following May, that journey ended at McAlister Field House, where—in many ways—it all began. Fears from the administration that we might act out proved unfounded. The class that arrived under fire left with grace.

Recently, I flipped through my copy of the Sphinx, the college yearbook. In it appear letters from both the regimental commander and the senior class president. Both include references to the unique and extraordinary challenges we faced during our time at The Citadel. They were challenges we didn’t choose but nonetheless rose up to meet. As previous classes have attested, the arrival of 1999 marked a break from the past. They can have the last class. We were the class that showed the way, that changed everything, the class that moved beyond what had been and came to exemplify all that would be.

We were the first class. We are 1999. And I wouldn’t change that for anything.

Kevin Hazzard is the author of A Thousand Naked Strangers, a book that Pat Conroy called a “shocking, utterly compelling tour de force.” His writing has appeared in Atlanta Magazine, Marietta Daily Journal, Creative Loafing, and Paste. Hazzard and his family live in Hermosa Beach, California, where he writes for television.