During Charles Foster’s sophomore year at The Citadel, Shine entered to blaze a new trail

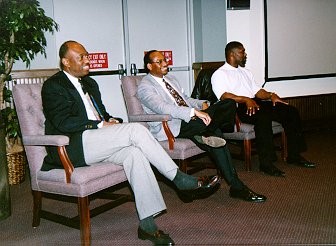

Nearly 14 years to the date of the sudden loss of Citadel graduate Joseph Dawson Shine, two of his classmates, Tip Hargrove and Jim Lockridge, came back to The Citadel to share accounts of their time with him at the college.

In 1967, Shine became the second African-American cadet to matriculate to The Citadel (after Charles Foster in 1966) and the only African-American member of the Class of 1971 South Carolina Corps of Cadets.

Fifty years after his matriculation, his Kilo Company classmates hosted a lecture in Bond Hall to reminisce about Shine and describe the perseverance and class unity it took for him to complete knob year to join the Long Gray Line with them.

“I have always wanted to share the Joe Shine story, but frankly, no one seemed to want to listen,” said Hargrove.

Hargrove, a lawyer based in Texas, said the idea of bringing Shine’s story to the forefront came after speaking with members of The Citadel African-American Alumni Association and hearing the complaints he sees on The Citadel Alumni Association’s Board of Directors about distance between white and black cadets at the college. As a graduate, he felt compelled to take matters into his own hands and try to do some good.

“As hard as the [college] administration tries to work on these types of problems, in my opinion, it comes across better from those of us who were in the trenches with a man like Joe,” said Hargrove.

Shine came to The Citadel after graduating from Charleston’s Immaculate Conception School in 1967. Despite tough beginnings during his knob year both due to his race, and the rigor of the Fourth-Class System in general, Shine left a lasting legacy at The Citadel. He was a distinguished student, having served on regimental staff his senior year, and a founding member of the college’s African-American Society.

“The truth is, Joe Shine’s example made the Class of 1971 a tolerant, understanding bunch, and for that we owe him a great debt,” said Hargrove.

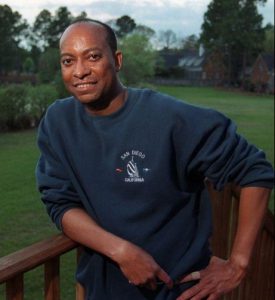

After graduating from The Citadel, Shine attended Harvard Law School and graduated in 1974. He later earned an MBA from Southern Illinois University and worked in the office of the Secretary of the Air Force. He was an attorney for the city of Charleston between 1976 and 1987 and then served as South Carolina’s chief deputy attorney general from 1987 until 1993 when he became the first legal counsel for the state’s Budget and Control Board. At the time of his death in 2003, he was general counsel for the Savannah River Site and newly appointed to the Citadel Board of Visitors by former Gov. Mark Sanford.

At the event, Lockridge, another 1971 graduate, shared his experience of being Shine’s friend and roommate for three of their four years at The Citadel. In the late 1990s, both he and Shine were interviewed by historian Alexander Macaulay for his book, Marching in Step, about their time together at The Citadel.

Lockridge recalled the story of being at a local bar with Shine, who was told that to be served he would need to move to the back of the establishment. The injustice Shine faced that night motivated Lockridge, editor of The Brigadier at the time, to pen a letter from the editor, entitled, “Rights Denied,” which called for a Corps-wide boycott of the bar.

According to Hargrove, plans to bolster their Shine tribute are in the works. Given the opportunity to speak about Shine’s legacy again, Dr. Larry J. Ferguson (Class of 1973) has agreed to be a part of the program as a close friend of Shine and the eldest living African-American graduate of The Citadel. Ferguson was also in attendance last week to pay homage to Shine.

Hargrove and his classmates could not let go the opportunity of getting a message out as “sorely needed” as that of class unity across color lines to The Citadel community.

“It’s funny, but to Kilo Company ‘71, Joe just became a classmate, not a black classmate, that’s exactly how it should have been,” said Hargrove. “When many of us got to school we saw the color of a person’s skin and made decisions because of it. But not when we left, for then we only saw one color—the gray of the Long Gray Line.”

The Citadel Regimental Band and Pipes to perform at The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in 2024

The Citadel Regimental Band and Pipes to perform at The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in 2024 The Citadel celebrates 25 years of women graduating from the South Carolina Corps of Cadets

The Citadel celebrates 25 years of women graduating from the South Carolina Corps of Cadets Upcoming News from The Citadel – March 2024

Upcoming News from The Citadel – March 2024